Okay, we’re not talking about the Aussie TV drama here. No, we’re talking about asset allocation. What proportion of your share portfolio you should consider having in NZ equities versus global equities. Once you have made the critical defensive/growth asset split, the next decision is how much to invest domestically as against internationally. This blog will focus on shares, but many of the arguments hold for property, bonds and cash.

Home Bias

Investors in most countries do have a significant allocation to their home market, compared to their country’s relative size in the global economy. The chart below shows the percentage the average investor has invested in their domestic equity market. For American and Australian investors it’s quite the majority – sitting at 79% and 66% respectively. The orange bars represent how large that market is as a percentage of the S&P Global Broad Market Index. This is what we call an investor home bias.

Many Kiwi investors fall into the trap of assuming; because the NZ market is a small percentage of the global economy, they should have limited investment in NZ shares. There are good arguments for and against this, which we will consider below.

Arguments for going global

Historically, many advisers and professionals have tended towards a large foreign equity allocation. This argument is typically based on the size and depth of the NZ market and our relative economic size. Here are four reasons often cited for going global.

NZ market is too small

If you are a multi-billion dollar fund manager, this argument might have some weight, but the NZX has a total free-float[1] market cap of $120 billion. Therefore it’s likely that the everyday investor will be just a drop in the ocean. If correctly invested, you’re not likely to suffer from illiquidity.

Even if half the equity allocation of all KiwiSavers was to NZ equities, this would mean New Zealanders collectively owned about 25% of the NZ stock exchange. The reality is, this ownership is closer to 5%. Increasing this wouldn’t be a bad thing and would probably encourage more companies to want to list publicly, something the NZX wouldn’t mind either.

NZ is too small relative to the world

The most common objection to investing in NZ equities is that we are a little group of islands and there is a big world out there to get a piece of. At 0.1% of the World’s listed companies, we have little influence or impact and so investors seek the world economic return.

Fair enough, we say. We get the excitement of big global multinationals and their ambitions. Except it’s the return on your investment that is important. Not whether you own 1×10-7% of NZ’s or 1×10-10 % of a foreign company.

Not enough choice in NZ

There are only 134 companies listed on the NZX main board and about 15 New Zealand companies listed on the ASX and not NZX (hey, Xero). The flipside is how many do you need to consider. Only about 70 of those listed have professional fund analyst recommendations (this is called “coverage”).

Naturally, the opportunity for diversification in NZ is lower, but good diversification only requires an avoidance of concentration. This can be achieved with as few as 12 companies, but ideally a few more.

Overall wealth allocation

As a counter to some of the arguments for investing in NZ shares, is that your overall wealth allocation is tilted to New Zealand economic conditions already. Your income is in New Zealand dollars, your job security depends on the NZ economy, your home or investment property is in New Zealand. This is a fair argument, however, don’t forget that many large New Zealand listed companies are significant exporters.

Arguments for staying local

Better tax treatment – a performance head start

The most boring but also most important point is tax. Any investment of significance outside Australasia is required to assume a 5% taxable dividend. This creates a tax obligation for those earning over $48,000 p.a. of 1.4% in a fund and 1.7% if held directly. That’s quite a hurdle to overcome in your total return. This deemed amount often exceeds any credits for foreign tax withheld.

Meanwhile, for a New Zealand resident investing in New Zealand companies, the imputation credits mean you are as likely to receive a tax refund. Within an unlisted PIE fund, such as Kernel’s, we also take care of all this, therefore not requiring a tax return[2].

NZ’s got performance & potential

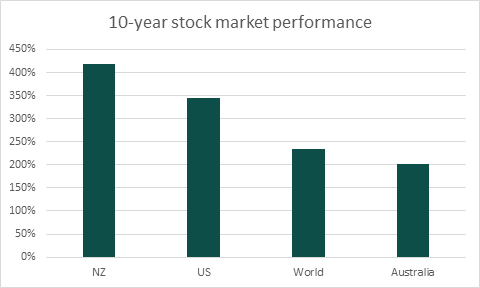

We downplay, whether knowingly or unknowingly, how comparatively stable and well-performing our economy is relative to others. Our S&P/NZX20 has had 10 year gross total returns of 417%, compared to 344% for the S&P 500, 201% for S&P/ASX 200 and 235% for the world overall. That is some pretty significant outperformance from little old NZ. Meanwhile, our volatility has been the lowest of all the above markets[3].

These figures are to the 31 May 2020, so including the impact of COVID-19 to date. Naturally, past performance is no guarantee of future results. Structurally, however, we don’t see obvious macro reasons to beat against NZ in favour of others.

This is where we are & you know it

You live here, you buy New Zealand products and the brands are familiar. For novice stock pickers, having a familiarity with the company and its products is an advantage over relying on the curated public information of a foreign company.

You, or people you know (hello NZ’s 3 degrees of separation), may work for that company and have a feel for its potential. Arguments about reducing systemic risk are muted by the increased interconnectedness of global markets and globalisation, showing through in the strong correlations between developed markets, especially in shorter periods.

Regional correlations are higher, but historic arguments for counter-cyclical economies seem to have diminished, at least in recent history.

Currency, cost & complexity

As soon as you are buying foreign shares or funds, you are introducing currency risk, global geopolitical risk and the difficulty and cost of accessing the global market. Many investors’ returns on the S&P 500, for example, were destroyed by a strengthening New Zealand dollar or doubled by its weakening. And predicting currency movements or the international flows of capital is true speculation. We don’t know how this will play out in the future.

Certainly, you can hedge or buy hedged investments, noting the higher cost or performance drag of doing so. For non-professional investors the costs of transacting and holding foreign shares can be high, or the currency conversion rate poor.

Patriotism

As the above chart showed, both Americans and Australians have significant home biases. Driven by the desire to own their own and benefit from the self-belief that their large companies will outperform on a world stage. So in addition to the more rational arguments for outperformance, there is the subjective argument to seize some national pride. You want to benefit as a part-owner of the success of our brands. We are passionate about New Zealand and hope you are too.

Designing your portfolio

Trying to provide some balance to the common arguments, we favour a mix of both local and global. Some global exposure is certainly good, but as you have read, don’t discount New Zealand too quickly. As to what the ‘magic number’ is when selecting your asset allocation – that’s the million dollar question. We’d love to know what you do in your portfolio.

[1] Free float means potentially available for sale and excludes the NZ government ownership of many utilities and key resources and the long term ownership by key staff/founders, such as Rod Duke of Briscoes or the Delegat family of Delegat wines.

[2] Assuming PIR is correct. This is not tax advice, as personal circumstances can vary, but is based on the most common scenario for investing $50,000+ abroad.

[3] Based on 10 years annualised risk (standard deviations) and performance from May 2020 S&P Index factsheets. “The world” is the S&P Global BMI.